After 30 years in Los Angeles, and umpteen of hiking the mountains that ring the San Fernando Valley, I finally made my first visit to the western rim, the Santa Susana Mountains. Here you can take the View down the length of the SFV, alias Sprawlsville USA, dba Home Sweet Home. This plain holds almost two million people, and is the main trunk watershed of Los Angeles.

I am a camera, and the camera is a water drop. This is what a water drop sees, landing atop the “Devil’s Slide”. Rejecting the fate of instantaneous evaporation in the scorched hills, it faces Plan B, percolating through the rocks, flirting with the lichens, rubbing against the oaks’ shady roots, then mingling with millions of other water drops, all squeezed up tight in a concrete straitjacket, taking the long slide down to Chatsworth, speeding on through Reseda, Van Nuys, Valley Glen, Valley Village, Studio City, Universal City and finally, forced through the Glendale Narrows in the hazy distance, to wherever that place “Los Angeles” is, that now claims it owns you and all your buddies.

Carey McWilliams famously called Southern California an “island in the land,” hemmed in as it is on all sides by rocky cliffs, abysmal chasms, anvil-like deserts, and a deep ocean with treacherous currents. Getting in or out of here, was historically extremely difficult. Santa Susana Pass Stagecoach Road, useable since 1861, was a breakthrough engineering feat that sped travel and commerce between the isolated southern and northern parts of California.

The famous Devil’s Slide was the last hurdle travelers from San Francisco or Santa Barbara had to face to get down into the Valley. Horses and mules were blinded, heavy wagons were winched and hoisted, ladies and gentlemen got out, tightened their bootlaces, and hiked, scrambled or fanny-slid down the scree slope to re-board the coach down in Chatsworth. This was how people got to Los Angeles for 22 years, until the Southern Pacific came in. The park is laced with faint stretches (unmarked) of this almost forgotten late Western horse-trail, or early California “freeway.”

These hills were the territory of the southern Chumash, and the rocky outcrops are reputed to shelter one of the largest and most artistically developed complexes of cave and rock paintings in North America. They are closed off and their locations are kept secret to all but the tribal members. They rue this state of affairs, and you don’t have to dig deep for the irony: Chumash culture can’t be understood or appreciated without people having access to it, but if they do, without very expensive security apparatus, they would almost certainly be defaced and plundered in short order. For now, we must let our imaginations run all around the rocks to find them.

They say one sign of incipient madness, is to see figures of gods, heroes, and mythic lovers suddenly appearing in the landscape. (For instance, envisioning in the boulders the mummified head of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III.) With an entrance gateway like Santa Susana Pass, it’s no wonder Southern California became known as the “Land of Fruits and Nuts.”

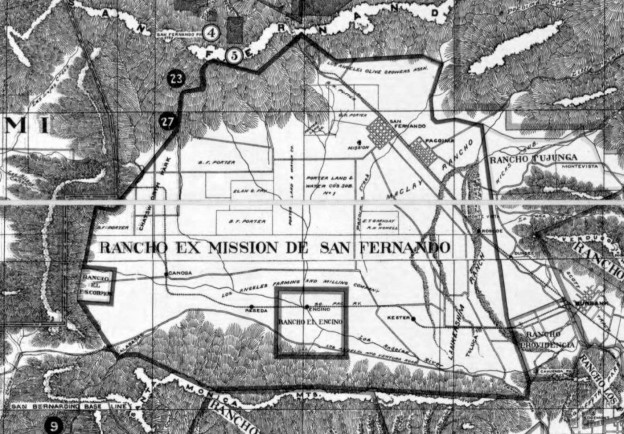

As beautiful as the landscape is, the Cal. Flor. Prov. at this park seems quite diminished; only a couple of interesting plants, amid a whole lot of ungrazed Spanish fodder. It makes sense, given the site’s history as a travel corridor (weeds weeds weeds) and the heavy grazing of the hills by herds under the Rancho Simi, Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando, and Rancho El Escorpion brands. Not to mention the years and years and YEARS of the Pass being used to shoot Westerns; much of this land was the old Spahn Movie Ranch.

But it also may reflect finances: this is a young park (1990s), and it was immediately threatened with closure by the Schwarzenegger administration under the ridiculous pretense that state parks were breaking the budget. The sword of Damocles is still officially over the park, which has no main entrance, signage, visitor’s center, water fountain, or historic / archaeological / ecological interpretation. Park on the road shoulder and hack across the chaparral, is the general access plan. Trail markers are unreliable and few. As with the Chumash Sistine Ceiling, I don’t whether, or which of, these fascinating road cuts are the Butterfield Stage Road; I don’t know where the Devil’s Slide was. I don’t know where the posse of Los Angeles Rangers circled the hideout of Juan Flores, capturing the notorious killer outlaw and his desperadoes. I don’t know where John Ford built and shot “Fort Apache”. But it was all in here, somewhere. It’s a fun place to let your imagination scamper.