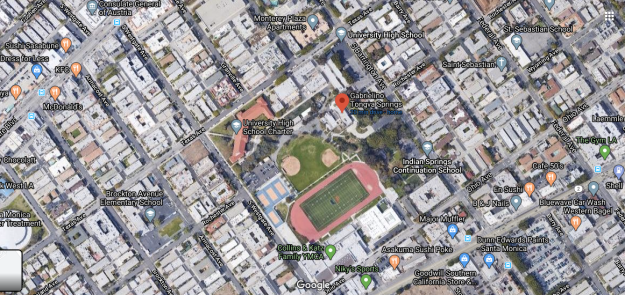

Easter Sunday, 2019, I drove to Santa Monica to sing with the Lutherans at St. Paul’s. I took Sepulveda Blvd., the route of the Portola/Crespi Expedition (only in reverse). Just before Santa Monica Blvd., I rolled past my very first apartment in LA (where I roomed with Glen Berger!) across the street from University High School.

I never ventured onto Uni grounds 30 years ago, but I’d since learned that there was an important old natural spring in there; some old guidebooks even called it “Serra Springs,” though another name was “El Berrendo Springs.” I thought I might glimpse it through the chain-link.

“Serra stopped here to say mass for the soldiers and sailors of the troop, beside twin springs which bubbled in beautiful pools. They looked liked two eyes, brimming with tears. In fact, they were like the eyes of St. Monica, weeping for the sins and lechery of her son Augustine. It was indeed May 4, and it was indeed the Feast of St. Monica they were celebrating. So Junipero on the spot blessed the place, and named the holy springs “Las Lagrimas de Santa Monica.” After Mass, they feasted, and a hunting party tried to bring down a deer, but it was only wounded. Curious Indians, drawn by the Mass, brought offerings of their own food, and there was much chaste bathing and fraternizing, and ever after, the creek and bay, and the meadow and the mountains all around the sea there, are called “Santa Monica.”

— Paraphrasing the story as generally presented. Some version of this story gets told in the official histories of the area. It’s what you’ll get online too, as of this writing. But it is confused.

The side gate was open for the gardener’s truck. So I parked and walked onto the school grounds. I asked the gardener about the Springs, and he kindly opened a gate near the athletic fields.

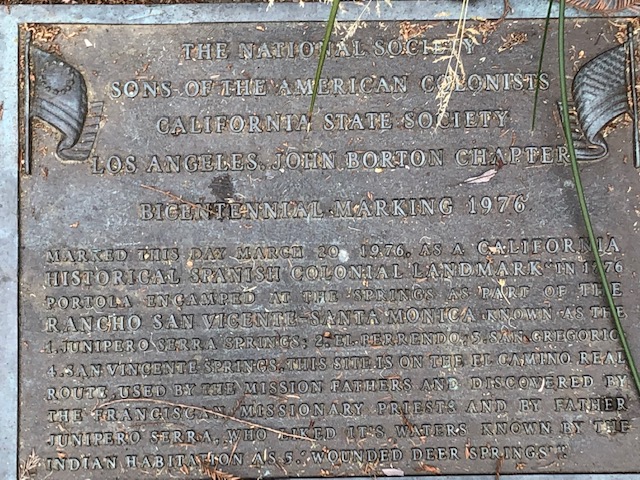

Obvious misinformation on the plaques gave me pause. One of them reads:

“Wounded Deer Springs – a village site of the Tongva Indians who enjoyed the waters and participated in ritual games as the original inhabitants of this area. Dedicated in their memory on October 27, 1979 by the University High School Warriors.” Another plaque gives the name “Serra Springs” along with “San Gregorio,” and “El Berrendo.” The Tongva never called it Wounded Deer Springs, and the Spanish never called it Serra Springs. Kuruvungna, the Kiij name for the spot, means “Our Place In The Sun.” El Berrendo” in Spanish means a pronghorn antelope. From some translator’s error, at some point, came the idea of the “wounded deer,” instead of a wounded antelope. But how did the area get finally dubbed “Santa Monica,” instead of, say, “San Gregorio?”

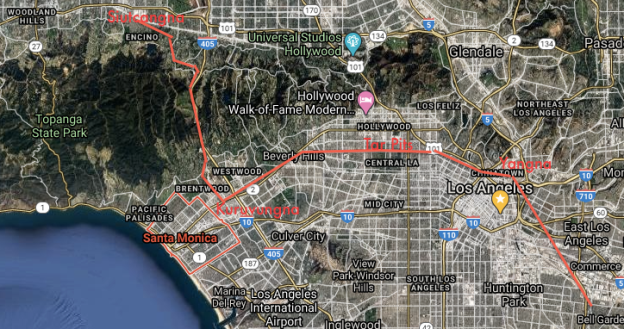

Coronavirus is a sweet muse, and now that I’ve had time to investigate a bit, the actual history of the site has become a bit clearer. First, look at the map:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/14qZBtlh6JOWTg29XVWeejZKe0OSBrwcv/view?usp=sharing

Kuruvungna sat beside springs, in a rose-perfumed glade shaded by sycamores. Today there are almost no native plants on the site, but the pictures below give an idea of how the flora of the place might have looked.

Tongva, or Kiij, (“we the people”) occupied the gentle slope to the sea, which we know today as Santa Monica, since at least 400 b.c.e. Year-round population in Kuruvungna may have been small; the site was cool and foggy in winter, and peripheral to the populous rancherias inland and to the east. But the springs were apparently a seasonal resort for certain summer celebrations, as the plaque describes.

News article below, from 2014. It tells how the campus once had many springs. Of the three left, one is so SNAFU the water has been diverted to the storm drains.

Fr. Juan Crespi, the Franciscan diarist of the Portola Expedition, describes the events of August, 1769 (not May, and not 1776) when the Spanish first introduced themselves to the Tongva. Read how the explorers, coming up from the south, first approached Yangna from the East LA side, and trembled at recurring earthquakes:

Notice that Fr. Crespi calls the springs San Gregorio; and that there was no mass said there. [The Feast of St. Gregory was celebrated in the 18th century on March 12; not in August, or as today, September 3.] Anyway, the next day, the expedition turned north over the hills (Sepulveda Pass) and found another Indian watering place, the warm springs at Encino, called Siutcangna by the Tongva. [The “great river” mentioned above is not the LA River, it is the Santa Clara.]

The Kiij at Kuruvungna knew no more of the Franciscans until two years later, when the wool-robes and leather-jacket soldiers came back and established Mission San Gabriel of the Earthquakes. They invited, then encouraged, then more or less compelled, all the Tongva – the people of Yangna, and Kuruvungna, and Siutcangna and all the rest – to abandon their rancherias and remove to the Mission site, and get to work. From 1771 forward, the traditional celebrations and festivities of the Indians, like those at Kuruvungna (whatever they were) were sharply repressed as heathen rites. You may View more about the process of conquest/acculturation/Christianization in my series of posts “The Theatre of Conversion…”

So if Crespi had, in 1769, called the place “San Gregorio,” and the soldiers had called it “El Berrendo,” after their lost quarry, where did the name Santa Monica come from? I believe, it was from somebody’s misreading of Fr. Crespi’s diary. If one reads months back in the journey, before the Portola Expedition entered the LA area, before they marched up from San Diego, before they even got out of Baja, and were somewhere south of Ensenada, we find a reference on May 4, the Feast of Santa Monica; but it is also the Great Feast of the Ascension of Christ, which would have taken precedence, and the Fray records saying Ascension Mass, as follows:

Note that the Baja site was merely a camping place, not a Mission site; and Fr. Crespi did nothing official about the name, he just says “we called it the Pools of Santa Monica;” he means the soldiers called it so. [If Crespi had come up with it himself, he would have said so.] Note that Fr. Serra, who this time WAS there, and kept his own journals, and always kept aloof of the “men,” called the place San Juan. Springs or pools in Spanish are “ojos” — eyes — and it may have been the soldiers’ pious joke to call places with weeping “eyes” after St. Monica, in oblique reference to the debauchery of her son Augustine. But neither Serra nor Crespi ever called any place in Alta California after Santa Monica.

FRANCISCO SEPULVEDA NAMES HIS RANCH:

With the Indians reduced (that is, concentrated, as in camps) by 1800, the plains around Kuruvungna were seemingly open real estate as the first land grants were doled out; but remember, the LA River ran nearby, and the City itself owned that watershed. In 1825 that changed; the river changed course, and all the hydrogeology of West LA changed, too, and the City’s claim to the lands of West LA and Santa Monica would have become dubious. [Also, after that earthquake, apparently, the third pool appeared. It was the Pool of St. Vincent: more on that, later.]

In 1839, Gov. Alvarado granted two Santa Monica ranches: the huge Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica; and the bijou Rancho Boca de Santa Monica. These are the first records in Alta California of “Santa Monica.” After these grants were named, not before, came the name of the Bay and the Mountains.

The big grant went to a Sepulveda, and the eastern border of his ranch became “Sepulveda Boulevard” going through “Sepulveda Pass” up past the “Sepulveda Dam” across the “Sepulveda Basin.”

“Francisco Sepúlveda (1775–1853), fifth son of Francisco Xavier Sepúlveda (1742–1788). The father was a Spanish soldier assigned to help found, and guard, the Pueblo of Los Angeles in 1781. Francisco Sepúlveda was born in Villa de Sinaloa, Mexico. He was six when he arrived with his mother and father in the Pueblo de Los Ángeles. He married María Teodora Ramona Serrano (1786 – ) in 1801. Francisco was regidor and acting alcalde in Los Angeles in 1825. In 1831 as a participant in the uprising against Governor Victoria he was imprisoned for a short period. He was commissioner at the Mission San Juan Capistrano from 1836 and 1837. The family moved to the west of Pueblo de Los Ángeles shortly after 1839 when Francisco was granted the 33,000-acre Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica by the Mexican government in recognition of his services.”

— Wikipedia entry on Francisco Sepulveda. His “services,” meaning, the secularization of Capistrano’s lands to deserving Californios. Didn’t the Padres teach, Manus manum lavat, one hand washes another?

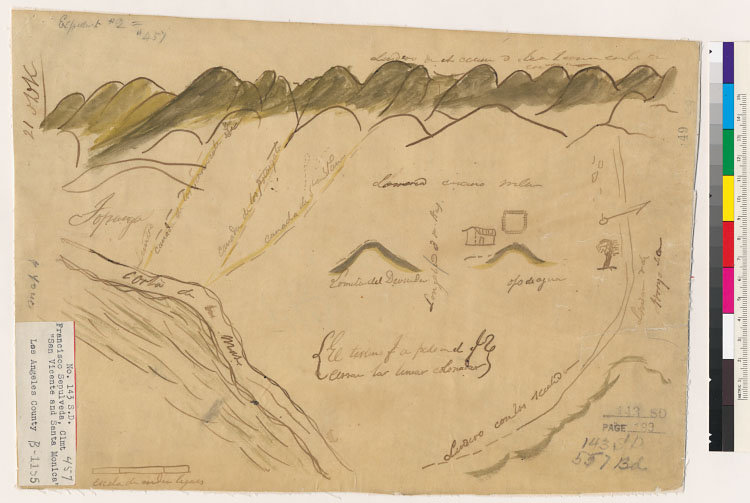

Note that Sepulveda was acting alcalde of the Pueblo in the pivotal year 1825, when the river changed course. Imagine him, then, soon after the earthquake, riding out with a small party to inspect whether the rumors were true, that the river changed course. Imagine him realizing the legal implications, perhaps re-discovering the pools if he had ridden there with his father or brother; or perhaps seeing them for (his) first time; and in general, liking the look of the land all the way down to the Westchester Bluffs. He would have to wait fourteen years, and go through much turmoil with California, before he would get his land grant, but he did, and it was he who named it for the pools, Los Ojos de Santa Monica. Nobody had published Crespi’s diary; clearly, Alvarado didn’t have a copy in the archives in Monterey. After 70 years, nobody in Los Angeles could have been aware of Crespi’s soldiers’ Baja joke, or of the remarkable wounded berrendo, or of a spring called San Gregorio. But to Sepulveda, an open field with weeping springs, begged to be named for Santa Monica. (A similar metaphor prevailed among the Chumash, whose word “Castec” or Castaic, as in Lake Castaic, means “eye of water”.) Here are the disenos of the two ranchos named for Santa Monica:

In the second Santa Monica grant, Gov. Alvarado gave the “Boca de Santa Monica” ranch to two couples to share: LA blacksmith Ysidro Reyes and his wife Maria Villa; and LA vintner Francisco Marquez and his wife, Roque Valenzuela. Both families were hijos de pais, unlike Sepulveda; they were born in LA, the grandkids of the early Spanish soldiers. (Theirs is the land in orange, above). What’s interesting is the name common to the two ranchos – but the reason for “Boca de Santa Monica” may be only loosely related to the weeping ojos on Sepulveda’s land.

The “Boca” grant contained Santa Monica Canyon, with an arroyo which cuts off the northern edge of the bluffs: the “Boca de Santa Monica.” This canyon was the Indian trail from Kuruvungna, down off the palisades onto the beach (Entrada Drive). Why is the Mouth of Santa Monica apt? We know the springs don’t feed the creek.

But the Santa Monica happens to be a creek which, notably, holds itself in restraint; it never gushes freely to the surf. Even today, it doesn’t reach the sea. The flow is stopped in the beach sand, a few yards shy of the ocean. ‘Rancho of a Woman Who Holds Her Tongue,’ is my translation of Reyes’s and Marquez’s “Rancho Boca de Santa Monica.” For here is another part of the legend of Santa Monica:

“Example of a Wife: The Church celebrates the relationship of the saintly mother and son, but what is often not stressed is that she was a saintly wife. She married a hot-tempered pagan, Patricius, and through her patience, perseverance, charity, and prayers, her husband did convert to Christianity on his deathbed. Set a guard, LORD, before my mouth, keep watch over the door of my lips (Psalm 141:3) Monica provided such a loving example of simply not reacting or criticizing her husband when he would lose his temper or verbally abuse her. Patience and gentleness moved him more than responding and criticizing.”

— From “Feastday Highlights,” Catholicculture.org.

In his diseno, above, Sepulveda drew a biased perspective to emphasize the plain as his portion. Still, it is is recognizable, with its dramatic backdrop of mountains. Note the little hill, atop which his adobe sits; and note, just under the brow of the hill, “ojo de agua” eye of water. This ojo de agua, was Kuruvungna Springs. And Francisco Sepulveda apparently lived just up the hill from it, and built one of the most famous ranches in California, about on the spot of my first apartment in LA, the Monterey Plaza, that 1980s monstrosity on Texas Ave., where I lived with Glen Berger, 30 years ago.

SO WHO WAS SAN VICENTE? WHY IS IT RANCHO SAN VICENTE Y SANTA MONICA?

Below is Tomas Giner’s 15th-century portrait of St. Vincent. Note the noose and the cross, symbol of the many tortures he endured in the stead of his boss, the bishop. Note also the dead Moor at Vincent’s feet. The message is the layman can also defeat the infidels, especially if they capture and torture you. Francisco Sepulveda had spent time in the hoosegow during the Californio revolt against Gov. Victoria; so it seems Sepulveda was claiming a share of Vincent’s victory as a “martyr” for California, and a share of Vincent’s comfort among sunshine and roses – roses like the ones that rambled around the springs.

“St. Vincent of Zaragosa, is the proto-martyr of Spain; that is, Hispania’s first Christian to earn the palm, during the Diocletian persecutions. St. Vincent was a deacon, thus a member of the laity who did his duty; he was the mouthpiece for his stuttering bishop. When the persecutors came, the bishop said, “t-t-talk to the l-l-layman,” and scarpered; St. Vincent faithfully faced down horrible tortures from the Romans, but never changed his message, that is, the word of his bishop. Vincent’s body was torn by hooks, roasted on a grill, etc., but still he mouthed sweet nothings of redemption. They stabbed him and threw him in a dungeon to crawl around on a floor filled with broken pot sherds; still he mouthed heavenly praise. While he was lying mutilated, he told his jailer he saw a vision of “a place filled with light, and filled with the scent of innumerable roses blooming all around.” The jailer saw it too, and became a Christian on the spot. Finally, Vincent’s mutilated body was thrown into a bog [sign of Celtic mythology] and all the wild beasts came to devour it; but his body was protected because the pool was guarded by a magical raven [Celtic Bran, god of silver-tongued bards].”

— My digest of the Life of St. Vincent of Zaragoza

St. Vincent, then, can be understood as the Spanish saint of “do your worst, I fought the law and I won, I got my repose, my sunshine, my pool with warding raven. Nobody can touch me.” That sentiment, a common one among the Californios, was, I submit, the reason he named the third pool, the new one, for San Vicente. Sepulveda was declaring his ranch was a repentance for (i.e., pride in) his dissolute youth (thus, the tears of St. Monica). It was also, he declared, the place of charmed protection from his persecutors (St. Vincent). I saw ravens at Kuruvungna Springs that Easter, but never suspected they were significant to that place’s legend.

SO WHO FOISTED OFF THAT OLD CHESTNUT ABOUT THE MASS OF ST. MONICA?

Robert and Arcadia Bakers’ real-estate empire bought out the old Sepulveda grant, including the Kuruvungna Springs, plus the Boca grant containing Santa Monica Canyon, in 1872. After 24 years of Yankee rule, the old ranch grants had finally won their long-delayed title clearance from the Washington, D.C. California Land Commission. Bringing Sen. J.P. Jones as a partner, the Bakers founded the City of Santa Monica in July, 1875.

Dona Arcadia remains an icon of matrist power. As formidable as Sen. Jones was, it was Dona Arcadia who named the city, laid out the city plots, and designed the Palisades. She directed the marketing of the place and its zoning, bullying Sen. Jones into accepting “Santa Monica” as a garden city, not an industrial powerhouse. She deeded much land to the U.S. government for the first U.S. Forest Station, run by her friend Abbott Kinney. And she gave some acreage away for the Veteran Soldiers’ Home and Cemetery, to lure retired invalid Civil War vets to move to Santa Monica for a new life and then drop dead.

Dona Arcadia was a terrible snob; in fact she was probably the last actual practitioner of the 16th century Casta system in North America, counting out her quarterings to assert her place at the top of the Mexican racial heirarchy. She lived until 1912, when both her city of Santa Monica, and her protege Abbott Kinney’s city of Venice, had become fashionable resorts of the Ragtime era. If any ice-cream suited, Wrigley’s gum-chewing American dared to ask if she were from “one of the old Mexican families,” she would apparently whip around and harangue the poor yokel for ten minutes on genealogy, in Spanglish, with how she was descended from lily-white Spanish hidalgos. She apparently became quite embarrassing.

THE FINAL VIEW: By the early 1890s, when Bancroft’s History of California had been published, and the incidents of the Portola Expedition were available in print, I think Dona Arcadia, or somebody close to her, found Crespi’s “Pools of Santa Monica” incident, either by flipping through the book or in an index. Not realizing that that incident was in Baja, or not caring, an enhanced version was hashed out, which became the official story – Serra, Crespi, the Ascension Mass, and the “Pools of St. Monica” all became conflated into a romantic story for her real estate promotion — a story which is still to be found in city histories.