Nature contributes the sea, the sun and the wind; but the astonishing gardens on the cliffs are the legacy of three fascinating individuals, each, in a way, a genius. Each is well-known in the history of the region, for doing other things. The garden was merely a happy accident in each of their lives, but in the view of posterity, these bluffs have become a grace upon the coast Southern California, and the credit of our gratitude is due.

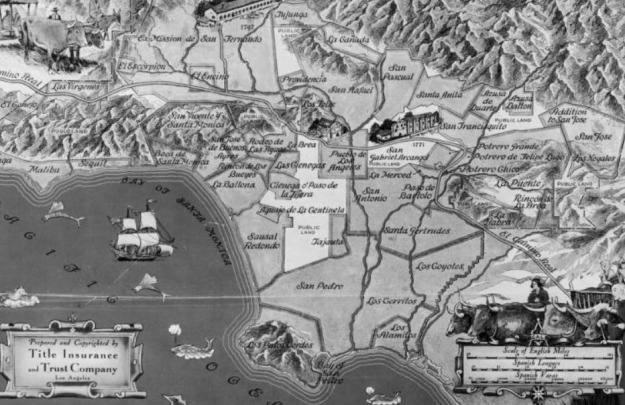

Until 1872, the mesas overlooking Santa Monica Bay were part of the Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica, the rich grasslands of the Sepulvedas; and Rancho Boca de Santa Monica, the equally lush ranges of the Marquez family. The vague grants overlapped by several thousand acres; and disputes before the (notorious) U.S. Land Commission were not settled until 1872, when the ranchos were consolidated, parceled, and sold off. The principal buyers had big plans for the sun-drenched coastal cliffs.

Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker

Sen. John P. Jones

Chief visionary was Dona Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker, a true grande dame, the social lioness of the Old Californio Families. Arcadia foresaw luxury hotels, wealthy retirees, and pleasure gardens in her new city. But her partner was mining magnate and Montana Republican Senator, John Percival Jones, who hoped to turn Santa Monica into the Entrepot of the Pacific, distribution hub of the combined products of North America and Asia. Jones conspired with the Southern Pacific’s Collis P. Huntington to build the Long Wharf rail terminus right at the bottom of the cliffs. They hoped a bustling port-railhead on Santa Monica Beach would eat San Pedro’s lunch (see “Los Angeles Harbor Fight.”)

“Santa Monica”

Eugene Morahan, sculptor. WPA, 1934.

These formidable speculators named their city, as did the rancheros, for twin springs (now on the grounds of University High School.) These wells had seemed to Fr. Juan Crespi in 1769 like two gushing eyes, “The Tears of St. Monica.” They formed a creek which flowed through Santa Monica Canyon, splitting the bluffs at its mouth (“Boca de Santa Monica”). This verdant canyon would attract our third genius to the shore of Santa Monica Bay.

Senora Baker had agreed with Sen. Jones that if he had his railhead under the northern bluffs, then the land of the southern bluffs would be given to the public forever as a promenade. Dona Baker then enlisted Abbot Kinney, the new California State Forester, to cover them with his exotic plants from all over the world.

Kinney was the apostle of the eucalyptus, that Australian import that he hoped would cover the “bare, treeless, arid plains” of California with marketable timber. Urbane, handsome and cultured, Kinney had cultivated the socially susceptible Dona Baker, and gotten her to grant him a research plot in Rustic Canyon, the first forestry research facility in the U.S. In gratitude he filled Arcadia’s public park on the bluffs with the exotic specimens of the Antipodes. The trees are now over a hundred years old, and gloriously sculpted by the constant Bay breeze into the fractal forms of frozen time.

Kinney’s hopes for eucalyptus as an American hardwood were dashed, as fast as a falling eucalyptus branch; the cracking, twisting, splitting wood is no good as timber. The legacy of Kinney’s crusade means a California plagued by useless and destructive, but beautiful, naturalized eucalypts; but it also includes the arboretum that is Palisades Park.

More fortunate, was that Sen. Jones’s Long Wharf also failed. Santa Monica never became the Gateway to the Indies; today the area isn’t choked by diesel and warehouses, but a world beauty spot. Maybe that became clear to the Senator, who also loved the bluff gardens, and reputedly came here every day with his dogs to watch the sunset, until the day he died.

Sen. Jones’s memorial, with traditional palm.

View south to Palos Verdes

…and north to Malibu.

The California Incline