OLD STOCK: I visited here back in December; I had a great time, but I thought the pics were too gloomy to share. Well, today we’re having the same gloom, and if I went today it would look just like this; so enjoy this post AS IF it were today. [“It’s Today!” — Mame Dennis.]

The Gold Line runs along here now. Note the old flour mill and the last old rail shed.

Down on what was once the sloping bank of the LA river, just above, and north, of where it used to flow past the LA Plaza; and right off the shoulder, as it were, of Chinatown; lies a length of land along the railroad tracks that was used by the Santa Fe Railroad for a half century or more, to store old rolling stock.

Here’s the State Parks’ history; and another from the DWP — both fascinating, fascinating.

https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=25964

https://waterandpower.org/museum/Early_City_Views%20(1800s)_Page_1.html

The hill, left, with lights, is Dodger Stadium. The route up there, past church, is the old Chavez Ravine.

Early, the site had been used by the pobladores to grow maize, which consistently still sprouted there; or else, alternate legend went, the early 20th c. Mexican population in nearby Aliso Gardens would guerrilla-farm maize, on plots scratched between the tracks. The two legends don’t conflict; nor does the legend that the left-over kernels from box cars used to haul corn sprouted (though much less likely to me; wheat, not corn, would sprout there.) But whatever, this long agro-industrial lot was called alternately, one of the two epithets in the title above.

Then the railroad was going to sell it for a 66-shed shipping warehouse complex. The citizens of Chinatown, and other nearby struggling neighborhoods like Chavez Ravine and Frogtown, fought and fought and (this a damn RAILROAD, remember, even in the 21st century they are thieves) fought and fought and fought for YEARS, and finally three years ago they won, and as of about a year ago, this is the emerald they have won for all Angelenos, Los Angeles State Historic Park. Ole.

The placards and the little shrine from the People’s Park victory are preserved on-site. Huzzah!

Archaeologically, this site is very important, for they discovered the original Zanja Madre, the “Mother Ditch” of Los Angeles, the original 1781 waterworks channel laid out by the pobladores to channel water from tanks upstream, near Elysian Park, along the wide but dry bed of the river, and into (and out of) a cistern the center of the Plaza.

La Zanja Madre….drains into here, at the end of the park! I guess it goes back into el Rio.

Because of the upstream advantage, there was a huge water wheel somewhere here for power-pumping. And the site was chosen by Don Abel Stearns to build the first flour mill in California, 1828 (?) right there on Spring Street with its wheels in the zanja channel, somehow contrived. (Don Abel; Yankee; not Jewish.) It continued as “Capitol Mills,” got generally absorbed into Chinatown for 80 years, and is now being renovated for condos. Thank the Angels they didn’t tear it down.

Thrilling to me, is that they have given downtown a glimpse of a re-wilded stream course, very chic, with granite benches down in the stream bed (instead of river boulders) and plenty of native plants, including tules, above.

Green, open space and wild-flowing water in the old LA river bed. This is a real gift.

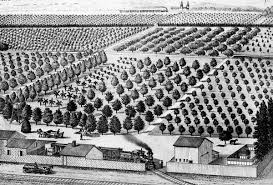

Most exciting of all, is that they gave over a long stretch of (well-irrigated) ground to planters holding an orchard of Valencia oranges, only a mile upstream from William Wolfskill’s Orchard, where the strain was developed in the 1860s, out of old Mission stock and fancy, smuggled strains brought by the Chinese. That there is a Valencia grove here, thriving for the community, within the very same river bottom and microrhyzal network from which the fruit first sprung, makes my heart sing.

They have graced the outside of each planter with a pithy reminiscence from the old-time locals who lived here, and who fought for this place, and who came to Los Angeles and made it better. Bless them, Angels.