I discovered this evocative photograph of the Valley (thank you KCET).

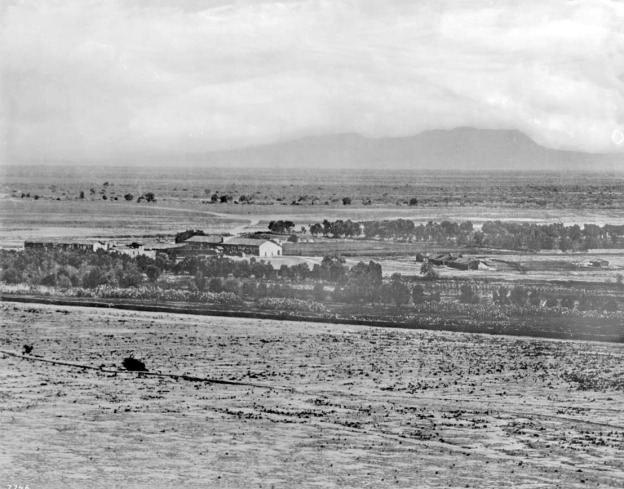

The view, taken on a cool drizzly day in 1875, is south, looking over what had been lands of the Mission San Fernando Rey de Espana, toward Mt. Cahuenga and the Cahuenga Pass. Los Angeles lies just over the hill.

The Valley was, in the Mexican period, historically contested land, the buckle of Alta California. One army could camp at San Fernando and the other at the Cahuenga Pass, and they could lob cannonballs and race squadrons of cavalry at each other across the Valley floor.

John C. Fremont would have seen it looking much like this on the rainy January morning in 1847, as he rode from the Convento toward Campo de Cahuenga to receive the surrender of Gen. Don Andres Pico, and end the Mexican War in California. In fact, as Fremont knew, the whole plain was Pico’s land, Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando. It must have especially galled Don Andres that Fremont and his Battalion of Bear Flag ruffians were camping there.

This view also was important to Gov. Juan Bautista Alvarado in 1836, during his coup d’etat. Southern Californios, led by the Pico Brothers and the Carrillo clan, had camped with their militia at San Fernando Mission. The rebels hoped to sever Southern California from the tyranny of Monterey, and to spite the treachery of Alvarado; but to do so they had to defend their capital of Los Angeles, and head off Alvarado’s Norteno army at the Pass. Bloodshed on this plain by fathers and sons on both sides was a real threat, but the Surenos finally acquiesced to Alvarado’s rule. Soon after, the land grants began, and the loyal Surenos weren’t stinted.

This strategic plain was also the site of the Californio rebellions against the Mexican Governors Micheltorena and Victoria. These Battles of Cahuenga and Providencia were violent and explosive, and they had real political consequences. But casualties were almost nil, intentionally, of course.

The land was shaped this way by the Franciscans, with orchards, arable, and rangelands. It was then managed by Don Andres Pico, and his mayordomo Valentin Lopez. Tongva and Tataviam Indians were the vaqueros and orchardmen who worked the ranch. It appears here roughly in the condition in which it was sold off by the Picos to Isaac Lankershim for his huge dry-wheat farms and farmstead tracts; and to Charles Maclay for his City of San Fernando. The line of oaks in the center marks the San Fernando Road.

This is the landscape as Collis P. Huntington and his SPRR engineers saw it. In fact this may have been a surveyor’s photograph: a year later, in 1876, they and thousands of Chinese workers drove the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad right down that line of oaks, along San Fernando Road, and changed this view forever.

The Mission lands ran to the line of mist before the hills. This is roughly the line of the Los Angeles River. Here, in the cool shade of Cahuenga, the beautiful mountain that looks like a lady lying down, was the Tongva Council Grove of Sycamores (by the Gene Autry National Center in Griffith Park.) Beyond the River, most of the hill-scape you see was Col. Griffith J. Griffith’s portion of the old Rancho Los Feliz. Today it is Griffith Park.

The Convento of the Mission appears still in good shape, but the church, the farmyard and outbuildings (including possibly the Andres Pico Adobe?) are muddy piles. Charles Fletcher Lummis would find the ruins in even worse shape ten years later. Appalled by the decrepitude of California antiquities, Fletcher founded the Landmarks Club to rally public forces in Los Angeles and across the nation to preserve San Fernando, and three other Missions.

Land that became North Hollywood and Valley Village appears here, at the center far right, between the orchards and the low-sloping Cahuenga Pass.