A new series applying history’s tire-iron to the rusty Hub of the Valley

PART ONE: ‘WHEN ALL THIS WAS FARMLAND’

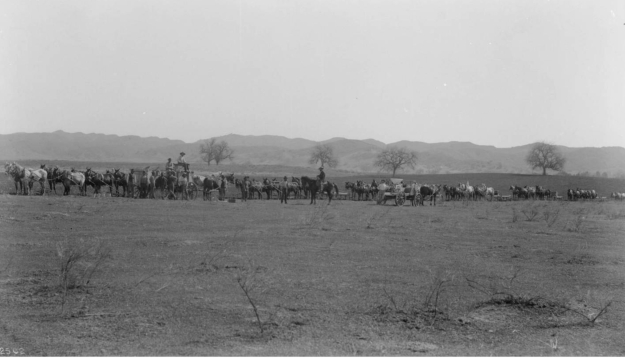

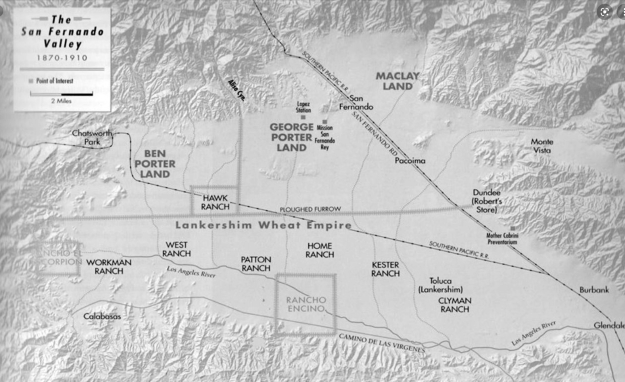

In the photo below, the sun-baked middle ground is today’s Van Nuys. Van Nuys is unusual in America in that the historian can’t sanctimoniously intone in the opening paragraph “For time immemorial People of the Ancient Ways called this land home, at one with Nature’s Ways.” Nobody called Van Nuys “Home” until Isaac Newton Van Nuys. And for the Tongva, the Chumash and the Tataviam who lived in the surrounding hills, the way to be at one with Nature’s Ways was to hot-foot it across the Valley as fast as you can in the dry seasons; and avoid it completely during the dangerous wet times when it swamped and Tujunga or Pacoima Wash could rampage. Of the two pleasant spots where natural wells and pools spring up, and the Indians had mixed-tribe rancerias, neither of them is Van Nuys. One was Encino [Siutcanga]; the other of course was San Fernando [Achoicomenga], where the Mission was built. But Van Nuys belonged to the antelopes. When the Indians were almost gone and the Mission was secularized the Valley was heavily ranched. Gen. Andres Pico took his interest in San Fernando and the northern half of the Valley, and his brother Don Pio Pico, the last Californio governor who had signed the original grant in 1846, by the 1850s had somehow come to own the southern half himself — including the cattle-tramped hardpan we call Van Nuys, that nothing in the middle:

Mission San Fernando and the vast San Fernando plain.hoto 1875 by a railroad surveyor; taken from SF Pass looking toward Cahuenga.

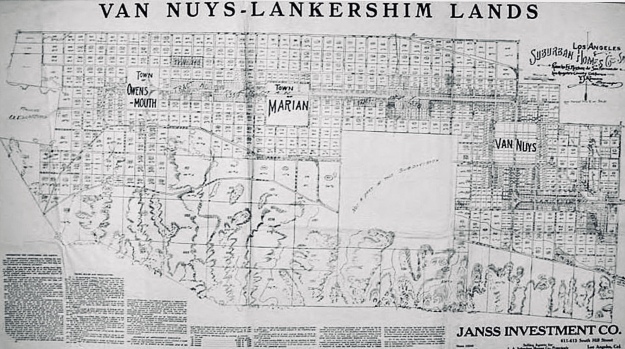

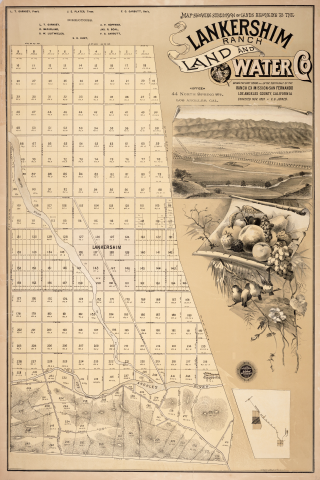

1869, the final surveyed boundaries of the Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando. Signed, sealed, and delivered by Pio Pico for $115,000 to the crazy Yankee wheat farmers.

Don Pio Pico, executing rights from a complicated chain-of-title victory from the Land Commission, sold his half of Rancho Ex-Mission San Fernando to the Yankees because beef prices had collapsed. Around 1865, the 15-year Gold Rush boom waned, then busted. The days were bygone of Valley rancheros driving thousands of cattle up to San Francisco and Sacramento to be slaughtered for twenty-dollar beefsteaks. The problem of a sudden oversupply of lowing stock solved itself, when a searing drought gripped the Southland, leaving the Valley full of cattle bones by 1868. The land sale was pervaded with ironies; Col. Fremont had made the Mission the headquarters for his California Battalion, and across these very plains had ridden in triumph to receive the sword of capitulation from Gen. Andres Pico, who claimed the Mission and its lands for his own. In 1848, Pico capitulated to save the Californios’ ranchos. Now the Picos were selling theirs off to the Yankees. But Pio Pico was the wiliest California land-jobber of them all. Realizing a profit from the switch of allegiances to Norte America, even so land could be liquidated legally, was their triumph. Pio was was certainly shrewd enough to realize a Hotel on the Plaza would bring steadier returns, and more genteel social connections, than running stock on the hoof. It was a brilliant trade for Pico, one of his canniest bets, for it kept him in good credit. It was also a decisive investment in downtown Los Angeles; the first moment when the dusty pueblo earned any notice at all in the world. Pio Pico put the Merced Theatre in back of the Pico House, with a door to the lobby; and put Jules Harder in the hotel kitchen; and made LA a city on the map.

And it was a great deal for Van Nuys, who was the partner responsible for actually running the farm operation. Lankershim had tried dry wheat farming for a couple of seasons but had busted. Van Nuys said he could do it, and he did; with true Yankee luck, the middle of 1870s when he experimented brought some good El Niño rains, and by the 1880s Van Nuys was harvesting boatloads of grain with Lankershim’s capital, and shipping it overseas at a branded premium. Thus it was a great return for the San Franicsco investors, too. Lankershim had found this land destroyed by heavy cattle ranching and failed to work it; it was Van Nuys who made it into a productive monocrop that brought other wheat farmers to make fortunes here too. He was one of the greatest farmers who ever lived.

The Home Ranch was the Van Nuys’ farmhouse, where he and Susannah (Lankershim) raised three kids and a million bushels of wheat.

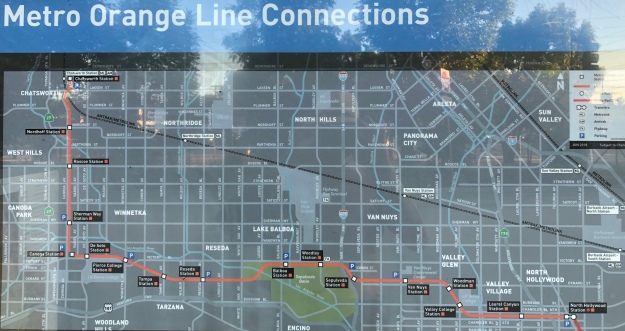

But who was Isaac Newton Van Nuys? He wasn’t the founder of Van Nuys, but it was named for him when he sold in 1909. (The town was founded in 1911). Speculative towns are usually named after the developer’s signature on the front of the check, not the farmer’s name on the back. Significantly, also, the name ‘Van Nuys’ is practically the only one of the developers’ original town names not to have changed; meaning, Van Nuys never actively voted to change its identity, as did social-climbing Toluca to Lankershim to North Hollywood, or Zelzah to Northridge, or Marian to Reseda, or Owensmouth to (the equally unappealing) Canoga Park. In the next part we’ll take the man, and his name, and his Life, in View, to glean what civics lessons we can.