In the spring of 1875, Eliza Tibbets carefully unwrapped the root balls of two seedling orange tree grafts she had received in the mail (via ship, train and stagecoach) from Washington D.C. Following the instructions of her friend, the USDA botanist William Saunders, she planted them in her yard in Riverside.

A few years earlier, Eliza and her (common-law) third husband, Luther Tibbets, had decided to close the dry goods store and leave Fredericskburg, VA. Both had been married before, with children; they were Swedenborgians, rapidly converting to Spiritualism, and ardent abolitionists and supporters of Reconstruction. [They have been described as “carpetbaggers.”] This didn’t make them popular in Fredericksburg, especially when Eliza’s son, James Simmons, fathered a little girl, Nicey, with a freedwoman. The whole family decided to leave town, Nicey included, and re-start life by pioneering in the genteel, free-thinking, arts-and-culture, gentleman-farming colony being planned on the romantic-sounding Santa Ana River, a town called Riverside.

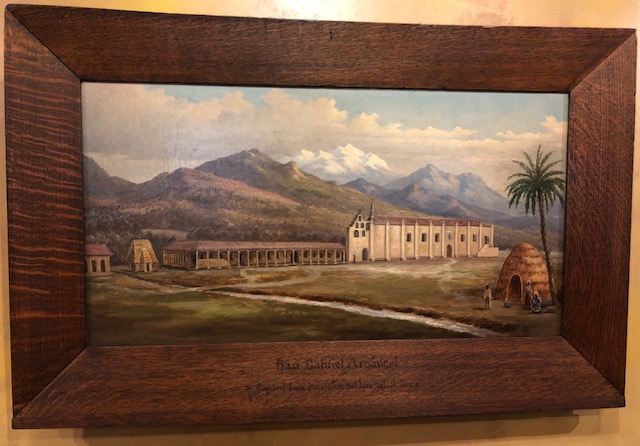

The settlement corporation’s brilliant scheme, hatched just after the Civil War in 1866, was to develop mulberry plantations, seed them with millions of silkworm eggs, and build up a sericulture in Southern California. This collapsed when the French worm-handler on the project, M. Prevost, the only one who knew silk, dropped dead in 1870. The land, if not the worms, was saved when statesman John W. North stepped in and took over the scheme. North had already founded Northfield, MN; and the University of Minnesota; so as freelance Founders go, he topped the A-list.

With the failure of silk in mind, Eliza stopped in Washington and asked Saunders to recommend a crop that would thrive in that climate. It was one of the very first real chances the USDA got to serve its purpose since Pres. Lincoln founded it: to help Homesteaders select crops, and aid them in developing scientific American agriculture across the range of our nation’s climates and soil types. It must be said, Mr. Saunders knocked it out of the park in recommending navel oranges to Eliza. The trees derive from a sterile spontaneous mutation, that just growed, from a rootstock in Bahia, Brazil. Mr. Saunders propagated samples of this unique variety, nurturing Eliza’s cuttings in the Smithsonian’s greenhouses on the National Mall.

Eliza knew she had to get the roots established in the hot hardpack, and since Riverside was so recently settled, it hadn’t yet finalized its irrigation system; she had to be as frugal as possible with water. So, the legend goes, Eliza saved up her dishwater each day and tossed it on the saplings. They grew in the California sunshine so quickly, and bore fruit so delicious, that all her neighbors asked her for cuttings. She obliged, not charging for the cuttings because, she reasoned, the U.S. government developed these on behalf of the whole people. 15 years later, there were half a million “Washington navel” trees in California, a quarter of a million of them within the Riverside city limits. Not only had the colony found its cash crop, the city had become the center of one of the wealthiest agricultural belts in the world, shipping sweet, seedless navels by the freight-car load. The colonist-neighbors of Riverside were millionaires!

Not the Tibbetses. Somehow — does it really matter how? — the family went bust in 1888. That same year, Nicey, who had grown up as Riverside’s first African-American citizen, died in a tragic drowning. [I like to imagine the little girl with a shovel and pail, helping her grandmother plant those first trees; or maybe helping her lug the basin of dishwater over to dump on the new “orchard.”]

The trees, which everybody in town seems to have always recognized are sacred, have been moved several times. In 1907 they were transplanted to the grounds of the Mission Inn — then still a little adobe guesthouse called the Glenwood Inn. For that re-planting, the spade was manned by Pres. Theodore Roosevelt, Himself. Sadly this tree doesn’t survive.

The sole surviving tree, the official Patent Washington Navel Orange, was moved to the completely unremarkable corner of Magnolia and Arlington, where it has been cared for by the UC Riverside.

Last year, the threat of the invasive Asian citrus psyllid forced them to erect a high-tech sun-permeable, insect-resistant screen. You really can’t see the tree at all, but it is clear that it is still being taken seriously as a scientific specimen.

Eliza was a colorful woman who epitomizes the legend of California as the “Land of Fruits and Nuts.” She certainly was eccentric, in her Queen Victoria drag. Riverside accepted her as a founding mother, and even supported her macabre career as a medium and seance-organizer, but was skeptical of her modern, un-churched mode of co-habiting, her progressive ideas, and her mixed-race family. She is remembered in the center of Riverside by a flamboyant bronze, “The Sower’s Dream,” by sculptor Guy Angelo Wilson. It is beautifully located, in an orange grove on the pedestrian mall outside the Mission Inn.

The statue is perfectly, extravagantly, bizarre, a figurative fantasy of Eliza’s gifts, rather than her realistic effigy. Spiritualist, progressive, matrist, pioneer, Lady Bountiful, Pomona, Mother Africa, Good Witch, Mr. Wilson’s vision of Eliza Tibbets’s inner beauty is an exceptionally sensitive tribute to her civic legacy.