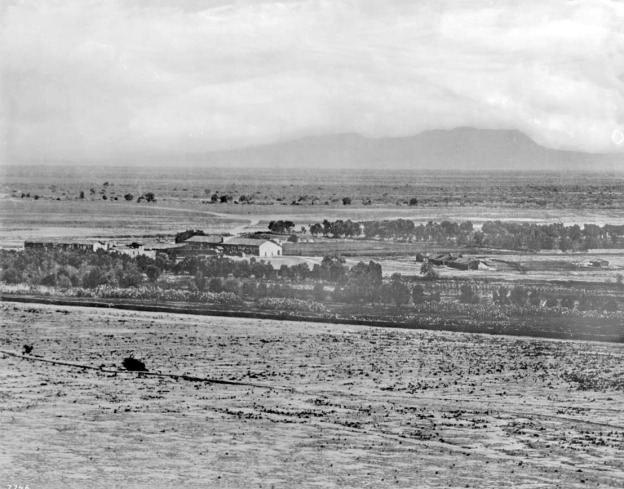

In the Golden Year, Aldous Huxley novelized the experience of being driven over Cahuenga Pass and down into the heart of the San Fernando Valley:

“Below them lay a great tawny plain, chequered with patches of green and dotted with white houses. On its further side, fifteen or twenty miles away, ranges of pinkish mountains fretted the horizon. “Whats this?” Jeremy asked. “The San Fernando Valley,” answered the chauffeur. He pointed his finger into the middle distance. “That’s where Groucho Marx has his place! Yes, sir.”

— Aldous Huxley, After Many A Summer Dies The Swan, 1939

At the bottom of the hill, the car turned left along a wide road that ran, a ribbon of concrete and suburban buildings, through the plain [Ventura Blvd.]. The chauffeur put on speed; sign succeeded sign with bewildering rapidity — BLOCK LONG HOT DOGS and BUY YOUR DREAM HOME NOW! And behind the signs the mathematically planted rows of apricot and walnut trees flicked past [NoHo, Studio City, Sherman Oaks] — a succession of glimpsed perspectives preceded and followed every time by fan-like approaches and retirements.

Dark green and gold, enormous orange orchards maneuvered, each a mile-square regiment glittering in the sun. Far off, the mountains traced their un-interpretable graph of boom and slump. “Tarzana!” said the chauffeur, startlingly; and there, sure enough, was the name suspended in white letters across the road. Meanwhile the mountains on the northern edge of the Valley were approaching, and, slanting in from the west, another range was looming up to the left. The orange groves gave place for a few miles to fields of alfalfa and dry and dusty grass. then returned again to groves, more luxuriant than ever.“

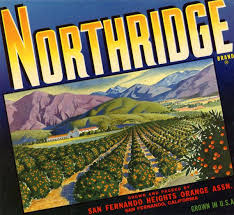

“The Citrus Belt complex of peoples, institutions and relationships has no parallel in rural life in America and nothing quite like it exists elsewhere in California. It is neither town nor country, neither rural nor urban. It is a world of its own.”

— Carey McWillians, Southern California: An Island On The Land, 1942.

“For the orange, as Charles Fletcher Lummis pointed out, is not only a fruit but a romance. The orange tree is the living symbol of richness, luxury and elegance. With its rich black-green shade, its evergreen foliage, and its romantic fragrance, it is the millionaire of all the trees in America, the “golden apple’ of the fabled Garden of the Hesperides. The aristocrat of the orchards, it has, by natural affinity, drawn to it the rich and the well-born, creating a unique type of urban-rural aristocracy. There is no crop in the whole range of American agriculture the growing of which confers quite the same status that is associated with ownership of an orange grove…to own an orange grove in Southern California is to live on the real gold coast of American agriculture.”

— Carey McWilliams

The last big grove of Valencia oranges in the Valley is this one, on the campus of Cal Sate University Northridge. Planted in 1940, it was already there when San Fernando State College opened in and around it, in 1952. The town of “Northridge” was originally named “Zelzah.” But in the early 20th century, Valencia orange farmers looking to make fortunes wanted to be on the right kind of land at the right elevation with the right soil, at the northern edge of the Valley. So to lure wealthy East Coast settlers to put in groves, the town changed its name to “Northridge.”

Rancho Los Encinos State Park maintains a small but lovely grove of Valencias, the orange that is LA’s pride.

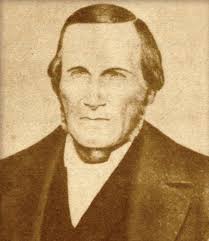

Few other American cities can boast that they are the native soil of a major agricultural crop. Los Angeles is the mother of the Valencia orange, and pioneer immigrant William Wolfskill was the father. A mountain man and fur trapper who settled in Taos in 1821, Wolfskill became a naturalized Mexican citizen, which meant he could own land. He arrived in LA in 1831, along the Santa Fe Trail. He passed through San Gabriel Mission; there he ate at Eulalia’s sumptuous table, talked with the curious Padres, and first laid eyes on an orange grove. These were the first oranges in California, planted in 1804 by the homesick Franciscans. Ten miles later, Wolfskill forded the muddy Rio de Los Angeles. It may have been a flash of vision and entrepreneurial inspiration, but he grasped that the lush river bottom lapping the edge of the sun-drenched adobe pueblo was the Garden of Eden, that here fruit of all kinds could be produced in abundance, and that there might be a world market for it. He settled in LA, and eventually bought Louis Vignes’s famous El Aliso Vineyards, which had been California’s original agribusiness. [Vignes had founded his winery under the shade of the mighty sycamore tree, El Aliso, that for generations sheltered the Tongva rancheria of Yang-na.]

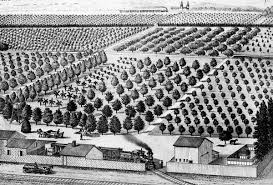

Those tracks would come to cover the orchards.

During and after the Yankee conquest, cultivating all kinds of crops, Wolfskill worked to spin the Franciscans’ abandoned orange trees into California gold. He turned the sandy flats east of the Plaza into California’s first commercial agricultural and horticultural laboratory. [Today, the nursery site is covered by Union Station’s sprawl of parking lots, trackbeds and platforms.] Using the Mission stock, selecting and cross-breeding with other, probably Asian strains, he created the perfect orange for Southern California’s foggy coastal valleys and cool, well-watered plains. Wolfskill’s career as an agribusiness tycoon put Southern California at the center of world commerce. As a bottom-line matter, consider that the Southern Pacific Railroad based its decision to come to Los Angeles on the economic potential of horticulture and produce freighting; and when they did, they laid the tracks and parked the depot adjacent to the orchard’s front gate for economy of shipping. [Somewhere in all this, probably when the depot was built, Yang-na’s sacred old El Aliso sycamore came down.] Wolfskill later developed groves south of LA around Santa Ana, laying the foundation for what became Orange County.

“Wolfskill was highly influential in the development of California’s agricultural industry in the 19th century, establishing an expanded viticulture and becoming the largest wine producer in the region. One of the wealthiest men of his time, he expanded his holdings, running sheep and cultivating oranges, lemons and other crops. He is credited with establishing the state’s citrus industry and developing the Valencia orange. It became the most popular juice orange in the United States and was the origin of the name of Valencia, California.”

— Wikipedia article on Wolfskill

“‘Of all the trees,” wrote Charles Fletcher Lummis,”that man has corseted to uniform symmetry and fattened for his use, none is more beautiful and none more grateful than the orange.’ It has certainly been the gold nugget of Southern California. Not only has it attracted fully as many people to California as did the discovery of gold, but since 1903 the annual value of the orange crop has vastly exceeded the value of gold produced. With an average annual income of one thousand dollars an acre, it is not surprising that the orange should be a sacred tree in California.”

— Carey McWilliams, writing of 1942 dollars