“Why be contented with one olive tree,

Wright and Forrest, “The Olive Tree” from KISMET

When you could have a whole olive grove?

Why be content with a grove, when you could have

THE WORLD –??”

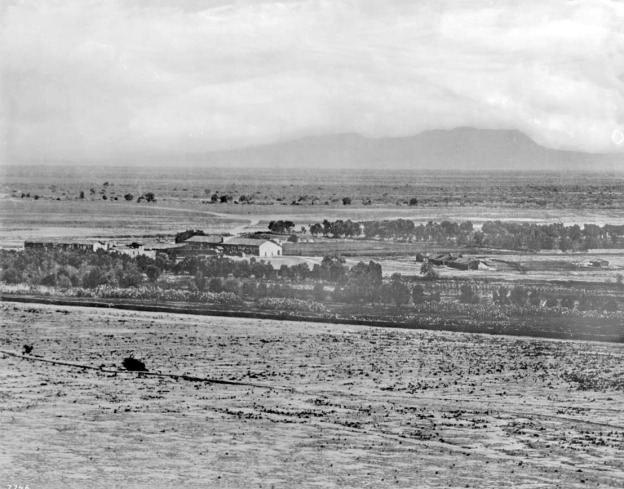

Around 1890, new Yankee cities were being carved out of the old Rancho ex-Mission San Fernando, and the smart money was clustered around the Southern Pacific right-of-way at the top of the Valley. The new rail cities became San Fernando and Chatsworth, and Sylmar and Pacoima. The big crop was olives; and many farmer-developers apparently made fortunes by pruning twigs off the old MIssion olive trees, rooting the cuttings, and re-planting the clones. In only a few years, the area had two or three of the biggest olive orchards History Has Ever Known.

The Franciscans’ Mission olives were planted for chrism, necessary for their rites. Olive, along with the Canary Island and Washingtonia palms, were introduced here for ritual purposes. And the sacred olives’ numerous progeny were eventually cured, branded, freighted down to LA in cans, then put on ships at the port of San Pedro. From there, they conquered the globe and Made Millions.

“In 1893, a group of Illinois businessmen purchased acres from the trustees of the Maclay Ranch east of the railroad tracks on San Fernando Road just south of Roxford Street and in 1894 began planting olives trees on up to 1,700 acres Experts were brought from France to supervise the work. Calling themselves the Los Angeles Olive Growers Association (in 1898 C.O. (Paul) Milltimore was the president and George L. Arnold the secretary), they built a packing plant and sold olives under the Tyler Olives label, later changing to the Sylmar Packing label. Sylmar’s olives became noted throughout the state for sweetness and purity. Chinese pickers were hired to harvest the crops, and up to 800 U.S. gallons (3,000 L) of olive oil a day were produced. The pickling plant was located on the corner of Roxford Street and San Fernando Road. By March 1898 about 200,000 trees had been planted,[15][19] and by 1906 the property had become the largest olive grove in the world. The first groves were planted with Mission, Nevadillo Blanco and Manzanillo olives.[15] Some Sevillano and Ascolano varieties were planted for extra-large fruit…

In 1904 the Sylmar brand olive oil won first place at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis, Missouri; in 1906 at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, Portland, Oregon;[23] and in 1915 at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.

— From the Wikipedia entry on Sylmar

As far as I knew, and I’ve stomped all over the area, the Mission groves, and the commercial groves, had all been subdivided and developed. How great my joy, then, to find these while I was walking from the Orange Line Station at Chatsworth, seeking out the trailhead to the Old Stagecoach Road. These gifts of the Greeks line the last 1/2 mile of the quiet, horsey backstreet that, I now realize, is really the first “in-town” block of Chatsworth, the flat block after the Devil’s Slide, along the route of the ol’ Butterfield Stage.

I have no other information about Farmer Gray, but I do know, that the Butterfield family got into olive ranching in the Valley in a big way. Maybe Gray was an associate, or a tenant of theirs, or maybe his venture inspired the family to go in big on olives. At any rate, these tree were rooted over a hundred years ago, and are genetically identical — in fact, the living branches and cells of — the trees that the Franciscans and their Indian neophytes pruned and tended with their Own Hands. Pretty darn cool..especially to walk home under, after a hike to the the top of the Pass.