PART TWO OF “VAN NUYS — A VIEWING”

Modern Van Nuys. Ike isn’t to blame for the blight and anomie. What’s a farm town without farms?

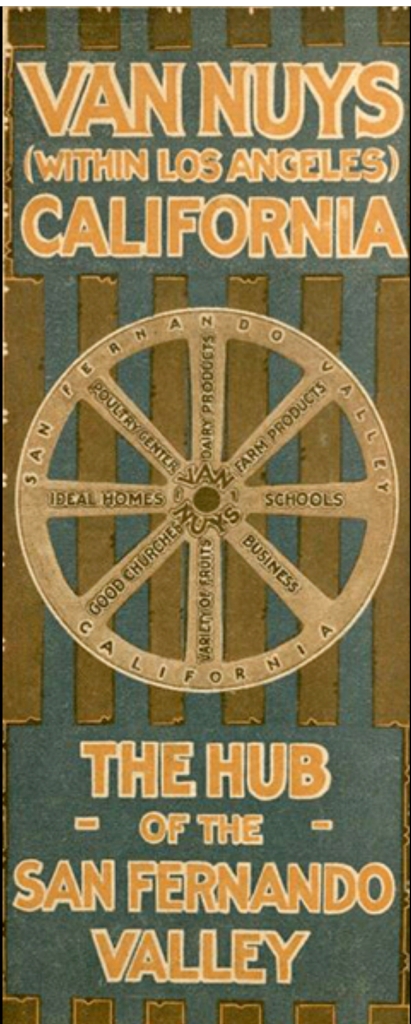

The Hub of the San Fernando Valley is flattered, frankly, to bear the Van Nuys name; this may be why it has never changed. (The View regrets the loss of Lankershim; but that burg went “Hollywood.” Show people, shudder.)

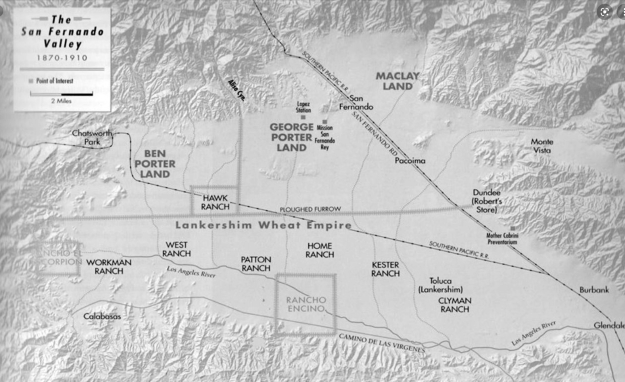

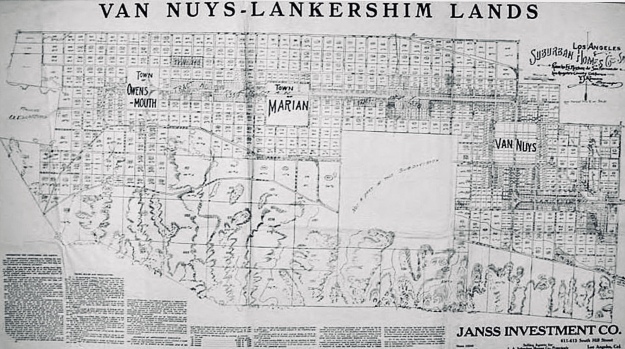

Remember Isaac was technically not the founder of the City of Van Nuys but the wheat farmer who sold out to the developers. Technically, too, there never was a City of Van Nuys; it is, and was planned as, Los Angeles. But Van Nuys knew this. He understood regional planning from the ground up and it is a mistake, as has been suggested, to think of him as a rube gulled by the Chandler syndicate or flattered into reducing his price by the developers’ offer to name the town after him. If anything, the Van Nuys and Lankershim names were premium branding; their commercial success (agro-biz) had made them rural celebrities at a time when almost 80 percent of Americans were farmers and 99 percent were desperate to get rich. The syndicate’s development planned mostly 40 acre farmsteads with strategically-placed small-lot market-towns. They hoped to attract young white Eastern farm families fleeing the frost, good kids starting out but who couldn’t afford land back home. Little capitalists — this was explicit — eager for a warm, sunny spot to claim their “little land and a living” (Bolton Hall’s phrase, meaning freedom through farming from debt and wage-slavery). Isaac Van Nuys signed off on, allowed his good name to be put on, plans for a modern, model farm-servicing and depot buckle in an integrated agricultural belt, irrigated by nearly free public water, main streets blazing with light at midnight, linked by clean electric rail, to serve a growing metropolis. Isaac was, individually and in partnership with his brother-in-law James Lankershim, already heavily invested in booming Downtown.

Mr. Harry Chandler with Gen. Moses Sherman

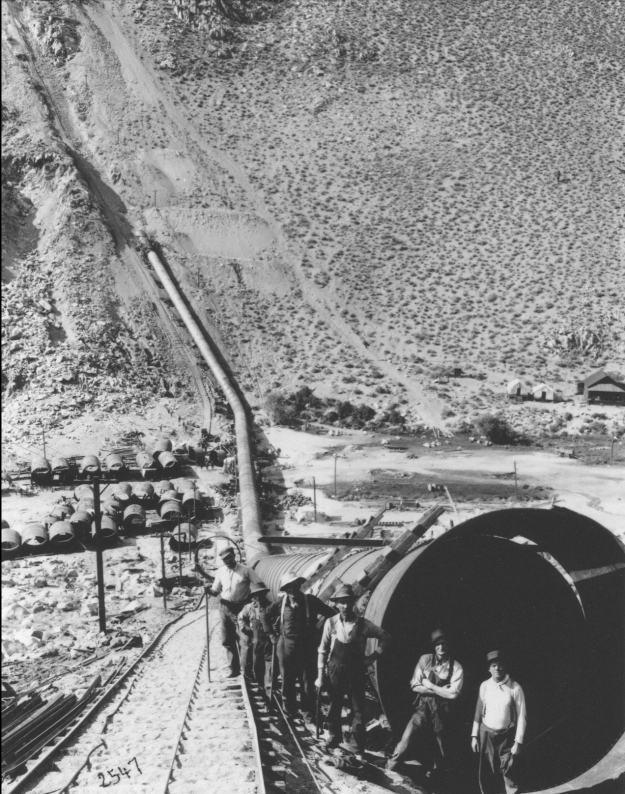

Ike had known and dealt with the Huntingtons for years as a leading farmer in Los Angeles County, through whose land passed the SPRR. He had bought (or, I believe, advantageously swapped for) the old Southern Pacific Depot on the old bottomland of the LA River downtown, so that his new grist-mill enterprise “Los Angeles Farming and Milling” could be most advantageously placed right on the tracks between the Valley and San Pedro. In this sense, he was one of the planners of the vision. So the Valley annexation plan as a whole and Van Nuys’s land sale were not “wheel estate” flim-flummery. Rather, all the players were informed by, and self-consciously in-line with, the most progressive, up-to-date, economic, organic and holistic urban design thinking of the time. Remember civic theorist Patrick Geddes?

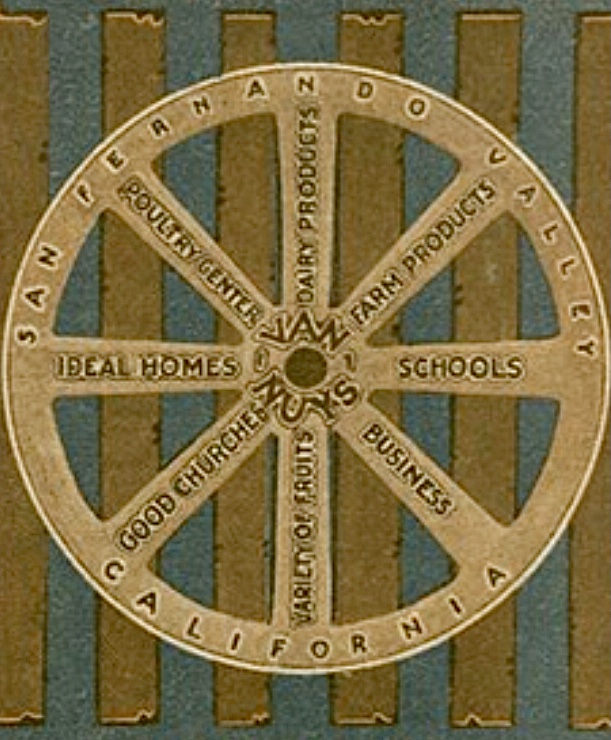

The drawing above is the famous “Geddesian Valley Section.” The other illustrations are also foundational to modern urban studies. Geddes wrote volumes of essential essays and studies, but his prose is tough sledding for laymen. His gift was inspiring an organic vision of cities through right brain engagement. The Boosterism of the Van Nuys promotional image may be corny, but it clearly reflects Geddes’s ideas.

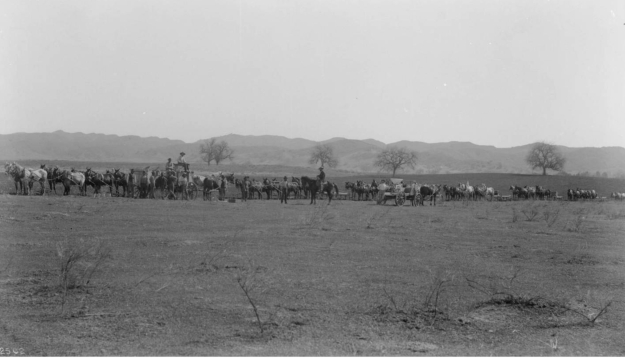

Van Nuys was a key part of a planned Greater Utopia, Ltd. But that meant, it was condemned from the start to be the dusty, Babbittty, railroad farm-town part of Utopia. By plan, Van Nuys was the back service porch of gilded Downtown Utopia, where the nobs would forever guzzle champagne, over the hill and far away. Van Nuys is a Potemkin prairie village: it would never, could never, grow to overtake Downtown in commerce and real estate values, no matter the citizens’ thrift or ambitious industry. Early investors might not have thought about it too clearly, but they could never hope that someday their corner of Van Nuys would be the new booming “Boardwalk and Park Place,” full of hotels. Van Nuys proved the point; Like Pio Pico before him, he brushed off his last ceremonial pair of dusty trousers — his hard farming days of handling a team of twenty mules from the dusty box seat of a combine had gone years ago— and he moved back to LA to throw his pelf on the pile Downtown. Ike spent the last year of his life in silk pajamas unrolling blueprints, planning to corner the era’s Boardwalk and Park Place, 3rd and Spring, supervising construction of this:

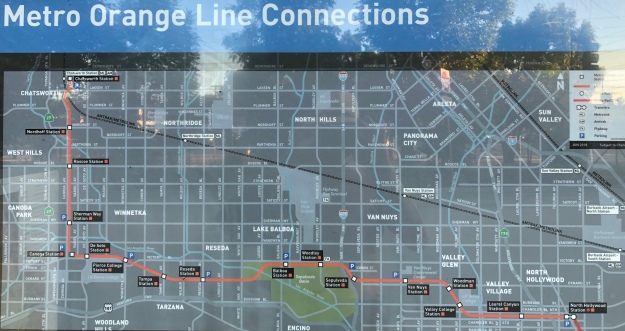

Van Nuys sold the ranch in 1909; the town opened in 1911, and Mr. Van Nuys died in 1912 — a few weeks before the I.N. Van Nuys Building opened. He died, also, a few weeks before the first Pacific Electric light-rail train arrived in Van Nuys and rolled passengers up Van Nuys Boulevard (then called Sherman Way). Ike possibly never set foot again in the Valley, never saw the new place called “Van Nuys.” He isn’t to blame for the sprawl, the blight, the anomie of today’s automobile graveyard Van Nuys. For Isaac, eternally, the town with his name was a four-square model farm town, with all the hook-ups a family needed to just move in and start plowing. And for years, it was.

The Jue Joe Ranch in Van Nuys. To Harry Chandler’s consternation, Chinese-American families were eager to live the Van Nuys lifestyle among their white neighbors. They taught LA a thing or two about how to handle the freshest fruit & veg in the glory days of truck farming. May those days come again.

Van Nuys The Man is absolutely absent from popular history as a personality — no memorable words, no bloviations on issues of the day; no hints of his pleasures and peeves, no memoir revealing his evolving sense of himself as a ‘player’; no scandals or rivalries in a town full of them. But this very absence to Modernity, is like the absence of sharp marble chips to a polished sculpture within. It reveals a hard core of values once so common-sensical and traditional they seem colorless today: he was sober, determined, loyal, ambitious, thrifty, patient, enterprising, dogged, nimble, polite, conservative, free-thinking, closed-mouthed, and open-minded. He was quiet and hoed his own row, minded his own family’s interests, yet everywhere he founded and built public things that made LA a first-class city and himself a millionaire. He was good with horses, a proud Mason, a father of three, and he made a fine husband to Susannah Lankershim, for whose mother’s sake he consented to become a public Baptist. He watched the weather, planted seeds and they grew. He was an upstate New York farmer from the old Dutch stock.

NEXT PART: How the name Van Nuys came to be permanently stamped on the dusty lower-left corner of our map, turns out to be a very rich land story indeed if we look into his Dutch ancestors’ experience, and Isaac’s own parents’ experience, and how they found land to farm. It is a Tale of Three Valleys — the San Fernando being the third. The progress of the Van Nuys family encompasses our whole history as an American people. It shows striking continuities, and illuminates pivotal moments in the rise of capitalism and modernity. It is the history of America itself. So View soon, THE HUDSON VALLEY VAN NUYSES…

Frank E. Schoonover