THE THEATRE OF CONVERSION, Part 6: Drama, Music, Art and Architecture at Mission Santa Barbara

Saint Barbara, with her Tower, is the patroness-saint of cannons and arsenals. Thus Gov. Felipe de Neve thought it a good name for the fortified presidio town he decreed in 1782, to control the Channel. It took four more years, and administration changes, for the Franciscans to get their chance to evangelize there. The Chumash lived on the beach at Yanonalit, the place of their chief Yanonali, and also in the islands nearby in great numbers, in great sophistication, and in great contentment. When the Franciscans trooped up the hill on Dec. 4th, the Feast of St. Barbara, to evangelize the Chumash, the friars relied upon their own arsenal: not bronze ordnance but bells, and a creche. Dec. 6th, only two days after the founding, was the Feast of St. Nick, or Sinter Klaas, and then, bang, it’s Advent. At Christmastide, Franciscans staged of colorful pageants to re-enact the story of Peace on Earth — angels, shepherds, Wise Men and all. Each night of Christmas there would be a choir outside the church singing Spanish songs — not Latin — and a simple mystery play with locals taking part as, for instance, shepherds adoring the creche. “Creche” derives from the Italian town of Greccio:

“Now three years before [St. Francis’s] death it befell that he was minded, at the town of Greccio, to celebrate the memory of the Birth of the Child Jesus, with all the added solemnity that he might, for the kindling of devotion. That this might not seem an innovation, he sought and obtained license from the Supreme Pontiff, and then made ready a manger, and bade hay, together with an ox and an ass, be brought unto the spot. The Brethren were called together, the folk assembled, the wood echoed with their voices, and that august night was made radiant and solemn with many bright lights, and with tuneful and sonorous praises. The man of God, filled with tender love, stood before the manger, bathed in tears, and overflowing with joy. Solemn Masses were celebrated over the manger, Francis, the Levite of Christ, chanting the Holy Gospel. Then he preached unto the folk standing round of the Birth of the King in poverty, calling Him, when he wished to name Him, the Child of Bethlehem, by reason of his tender love for Him.“

— St. Bonaventure, The Life of St. Francis of Assisi

Santa Barbara has set up its creche, with live ox and ass, or at least sheep and donkeys, since the 18th century. It ought to be remembered that domesticated stock animals like sheep were completely alien to California. It must have taken years for even motivated and observant Chumash neophytes to understand the associations between these bleating sheep with their wooly fleeces, and the approved lowliness of the shepherds in the Nativity story, and the god in the manger, and the fine gray woolen robes the Franciscans wore, and the coarse, scratchy white ponchos and pantaloons all neophytes would be forced to weave and wear and wash, too. The Christmas shepherds’ gift to the proudly naked Chumash, it turned out, was laundry.

The Franciscans evangelized here as they had in Spain and Mexico for centuries; at Christmas that meant staging a midnight pageant, in a tabernacle, or on the front steps of the town church. In many cases in Italy and Southern Europe this had been an old Roman temple. Thus it is likely that the wide front porch, and the serene Classical facade rising behind it like the scaena in a Roman theatre, were at least in part designed, or at least used, for the staging of pageants, proclamations and concerts. We know that the Franciscans enacted these Christmas plays out of doors. Versions of these plays survived in Santa Barbara from oral traditions brought from Mexico. They are among the very few literary productions of Alta California.

La Pastorela, the Shepherds Play, was written down from memory by Pablo de la Guerra in the 1860’s. It has been revived and is performed in Santa Barbara every holiday season. It tells the adventures of three shepherds, traveling the road to Bethlehem with their gifts for the manger. (Franciscans also produced pageants of the Three Kings, the Flight into Egypt, etc.)

PREACHING TO THE CHOIR

St. Francis was a former troubadour, sang incessantly, and composed songs and canticles. Music and common musical celebration, i.e., singing together, are indispensable to Franciscan Christianity. This was even more important in California, where, not surprisingly, those Indians with the greatest aptitude for music were the Indians who learned Spanish the fastest.

“The scarcity of first-language Spanish speakers at the Missions — customarily consisting of the priests, a mayordomo, and three or four soldiers for a guard — meant that musicians had the greatest access to priests and thus greater exposure to Spanish language than did other Indians. Music instruction, rather than formal education, had been the aide for language adoption….By joining the choir, Indians had chosen to learn the new music and to learn enough Spanish to cooperate with the priest in their joint venture. Although Indians learned from the priest, they shared their talents with him. Reciprocity, rather than simple dominance, characterized these clerical events.”

— James A. Sandos, Converting California, 2004

Thus in California, building a fine neophyte choir for each Mission was among a missionary’s proudest achievements. (All agreed the finest choir was that led by Fr. Narciso Duran, at Mission San Jose.)

Fr. Duran strikes up the band at rehearsal; and rewards a singer with a piece of fruit, for blending.

Plainsong is words set to music; to learn the music, learn the words.

Even the most advanced European masses and motets were performed at the Missions, as proved by the scores found in the music libraries. European explorers and visitors to California, who had heard choirs and orchestras in Paris and Rome and London and Madrid and Mexico City, remarked on all the Mission musicians with favor.

“The most outstanding trait of these Indians is their inclination for music. In the missions they learn soon and easily to play the violin, the cello, etc., and to sing together in such a manner that they can perform the music for the Mass of a very complicated harmony, certainly better than the peasants of our land could learn after years of study.”

— Pedro Botta, doctor on a visiting French ship. Cited by James A. Sandos in “Converting California”, 2004

Leather-head drums, the vaquero’s Spanish guitar, the Presidio’s hot Spanish trumpets, the shepherds’ horns and pipes, the bass viol and bass guitar, even the keyboards in the form of the quasi-mythical San Jose organ, all came together in the California Indian Mission Band. And this musical seed burst into musical fruit out on the Ranchos, a century later. The Missions are the real mothers of American Western Music.

BUILDING AND DECORATING THE MISSION

Santa Barbara was Fr. Lasuen’s homage to the mother church of Mexico, the Metropolitan Cathedral on the Zocalo in Mexico City, the church and plaza decreed by Cortes upon the ruins of Tenochtitlan.

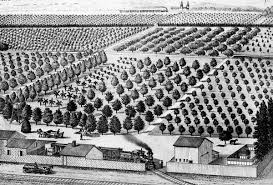

Santa Barbara Mission was founded by Fr. Fermin Lasuen, the second Father President of the Missions. a Basque recruited to the College of San Fernando in Mexico City. He was the real father of California vernacular architecture. Lasuen transformed the tule-thatched, stockaded missions into the architectural emblems of Spanish California. Lasuen specially recruited European colonist-master-craftsmen. Here, as later at San Fernando, guild carpenters, stone-cutters, masons, sculptors, music masters, instrument makers, and choir directors, from France, Spain, and Italy, taught Chumash artists 18th-century European artistic techniques.

The dado has extravagantly psychedlic marbeling that blends to a golden shimmer, suggesting irridescence.

The pilasters and cornice are painted rose and white to recall porphyry.

Chumash decorative skill and artistic traditions, applying Vitruvius’s Roman rules, made Santa Barbara, appropriately, the real bombshell of the Missions. Coast Chumash have one of the most ancient and developed fine arts traditions of all the Southwest tribes, including symbolist religious painting, rock and sand paintings, groovy and intricately executed body art, and imposing stone carvings. A Chumash neophyte at Santa Barbara produced the very first European-style sculpture in California. Lions in fountains is an old Spanish trope; but here it is a Native American animal, Puma concolor, stylishly interpreted by a Native American artist. Later Chumash artists added allegorical statues to the facade.

Of all the Missions, only Santa Barbara managed to survive Alta California’s chaotic history more or less intact, with Franciscans serving mass on-site, from the 18th century to today, through lean times and fat. As the other Missions were abandoned after secularization, the padres at Santa Barbara worked to preserve their libraries, archives, and as much as they could of the art and more or less gilded liturgical paraphernalia. This allowed Santa Barbara to excel in another European art, that of history. Most of the finest Franciscan historians of California have been brothers at Santa Barbara, including the famous Fr. Zephyrin Engelhardt.